The Drama and History Behind The Stories

The Story Behind Masque of Honor

On February 6, 1819, there was an infamous duel between second-generation descendants of founding father George Mason IV: Armistead T. Mason, the original builder and owner of Selma Plantation, and his second cousin and brother-in-law, John Mason McCarty.

We won’t spoil the ending by telling you who lives and who dies, but if you’re already in the know, you may enjoy reading Jack’s daughter’s memoir.

Masque of Honor, tells the story of two cousins, members of Virginia’s elite aristocracy, who turn against one another over power, position, and politics.

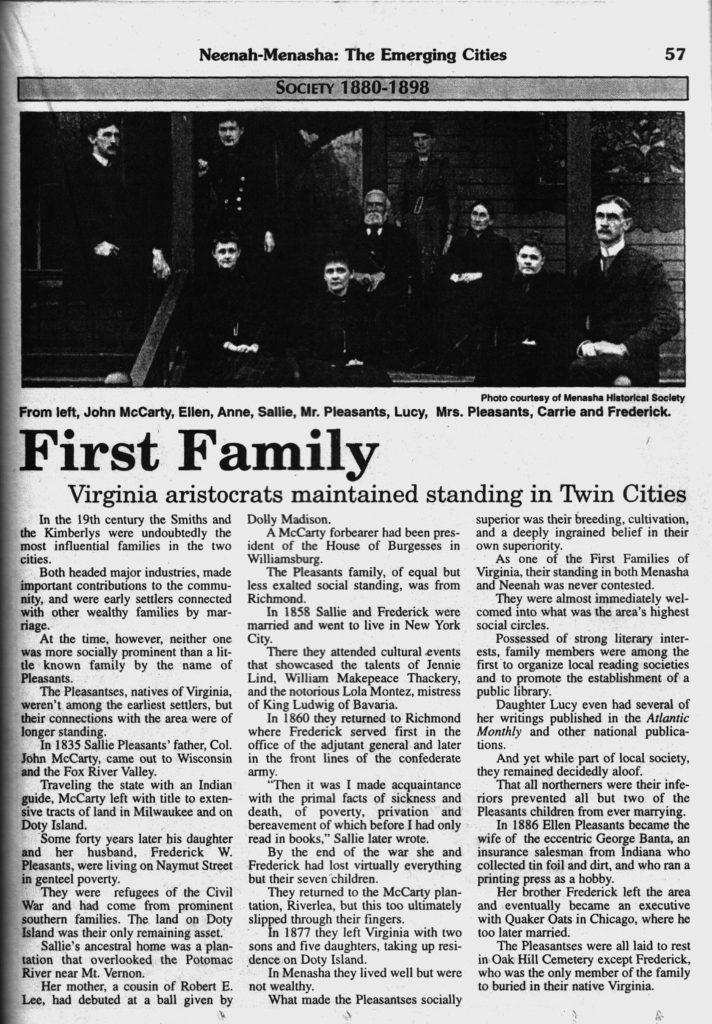

An account of the Mason-McCarty duel is told first-hand by Jack McCarty’s daughter, Sally McCarty Pleasants, in a letter written from her home in Menasha, Wisconsin on December 31st, 1899. I would like to personally thank Jared Banta, Jack’s great, great, great, great Grandson, for providing me with this family account. Read Sally’s Memoir

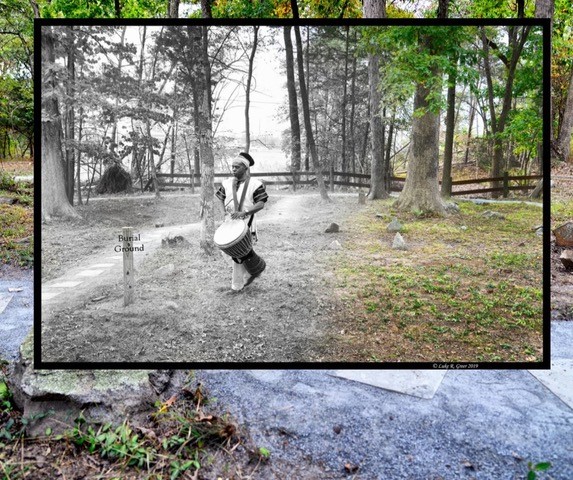

REMARKS FROM THE BLESSING CEREMONY HELD AT BELMONT PLANTATION BURIAL GROUNDS

My interest in the plantations of Belmont and Coton Farm initiated from my research in writing of an historical fiction that tells the story of two men embroiled in a bitter dispute that resulted in an infamous duel. One of those men, Armistead Mason built Selma. The other, Jack McCarty married the youngest daughter of Thomas Ludwell Lee of Coton Farm, Belmont’s sister plantation which sat not a half mile from this site.

I’d like to read a passage from my book, where Jack had set out on a trip to Natchez Mississippi to explore a new business venture.

“He saw them again, the enslaved men—barefoot, manacled and chained together in double files under the close supervision of mounted drivers armed with both guns and whips. Women, too, were walking in bare feet with tattered skirts caked in mud while children and the invalid rode in the wagons that accompanied the coffle. The group had been walking for weeks through Tennessee and down the Natchez Trace. They were filthy, exhausted and scared out of their wits as to the uncertainty of their fate. The silence of their inhumane treatment screamed at him; their suffering obvious as they shuffled and clanked down the road. Jack was appalled. What he witnessed horrified and sickened him. For the clean, well-groomed men he had inspected earlier at the Forks-in-the-Road markets resembled nothing of the cruelty bestowed onto those in the caravan that hot summer afternoon. For days, he couldn’t sleep and still the visions of their anguish haunted him. Never again would he condone the practice of selling slaves away from their Virginia homes.”

I am NOT a historian. My words are fiction, but the story in this passage is rooted in truth, recorded in memoirs of Jack’s life and the accounts of others who bore witness to the coffles heading to Natchez Mississippi. Although there are no records of Jack McCarty engaging in the slave trade after his Natchez trip, his brothers-in-law did, selling enslaved men and women from Coton Farm and other Virginia plantations to the markets at Forks-in-the-Road and transporting them in the manner I describe.

This why our family foundation is supporting the work of the Freedom Center and other organizations dedicated to the preservation of historic sites and the telling of stories such as these so that we never forget.